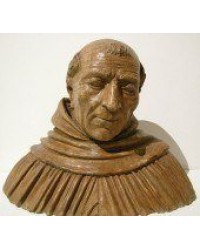

Albertus Magnus

St. Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-1280), Dominican bishop and philosopher best known as a teacher of St. Thomas Aquinas and as a proponent of Aristotelianism at the University of Paris. He established the study of nature as a legitimate sciencewithin the Christian tradition. By papal decree in 1941, he was declared the patron saint of all who cultivate the natural sciences. He was the most prolific writer of his century and was the only scholar of his age to be called “the Great”; this title was used even before his death.

Albertus was the eldest son of a wealthy German lord. After his early schooling, he went to the University of Padua, where he studied the liberal arts. He joined the Dominican order at Padua in 1223. He continued his studies at Padua and Bologna and in Germany and then taught theology at several convents throughout Germany, lastly at Cologne.

Sometime before 1245 he was sent to the Dominican convent of Saint-Jacques at the University of Paris, where he came into contact with the works of Aristotle, newly translated from Greek and Arabic, and with the commentaries on Aristotle’s works by Averroës, a 12th-century Spanish-Arabian philosopher. At Saint-Jacques he lectured on the Bible for two years and then for another two years on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, the theological textbook of the medieval universities. In 1245 he was graduated master in the theological faculty and obtained the Dominican chair “for foreigners.”

It was probably at Paris that Albertus began working on a monumental presentation of the entire body of knowledge of his time. He wrote commentaries on the Bible and on the Sentences; he alone among medieval scholars made commentaries on all the known works of Aristotle, both genuine and spurious, paraphrasing the originals but frequently adding “digressions” in which he expressed his own observations, “experiments,” and speculations. The term experiment for Albertus indicates a careful process of observing, describing, and classifying. His speculations were open to Neoplatonic thought. Apparently in response to a request that he explain Aristotle’s Physics, Albertus undertook—as he states at the beginning of his Physica—“to make…intelligible to the Latins” all the branches of natural science, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, astronomy, ethics, economics, politics, and metaphysics. While he was working on this project, which took about 20 years to complete, he probably had among his disciples Thomas Aquinas, who arrived at Paris late in 1245.

Albertus distinguished the way to knowledge by revelation and faith from the way of philosophy and of science; the latter follows the authorities of the past according to their competence, but it also makes use of observation and proceeds by means of reason and intellect to the highest degrees of abstraction. For Albertus these two ways are not opposed; there is no “double truth”—one truth for faith and a contradictory truth for reason. All that is really true is joined in harmony. Although there are mysteries accessible only to faith, other points of Christian doctrine are recognizable both by faith and by reason—e.g., the doctrine of the immortality of the individual soul. He defended this doctrine in several works against the teaching of the Averroists (Latin followers of Averroës), who held that only one intellect, which is common to all humans, remains after the death of man.

€4.91 (9.60 лв.) €6.14 (12.00 лв.) Ex Tax: €4.50 (8.81 лв.)